We’re talking about Mosimann’s of course! As I walk through the doors of The Belfry that have welcomed many a pair of famous feet, I’m warmly greeted, offered a blazer to exchange for my coat (you are not to be seen here without one), and ushered upstairs to the bar. The dining room below is empty bar a trio of white-haired and venerable-looking gentlemen slowly working through their late lunch.

In terms of the club itself, the first thing that’s noticeable as I’m shown around the place is the sheer grandness of it. The restaurant was a former church put there in 1830 so that the local aristocracy had somewhere to go on Sunday mornings. It stayed that way for 100 years and changed hands a few times before becoming the Belfry Club in 1947. Anton Mosimann had already taken a shine to the place, and was keen on calling it his own. He did so in 1988.

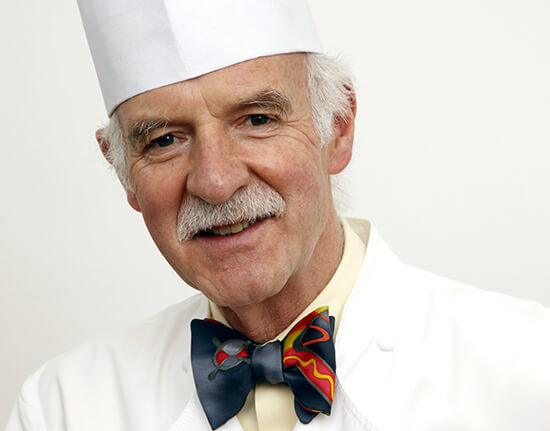

At the time, Anton’s sons Philipp and Mark were adolescents, but would later become an integral part of the family business. Mark tells me about the inception of the Mosimann enterprise.

‘Father was invited here back when it was the Belfry Club and just fell in love with the space and the building. That was when he’d been at the Dorchester for 13 years and was open to refurbishment. He started thinking about the possibilities with this place. All the private rooms were originally offices, so he converted them all into private dining rooms, which he got sponsored by luxury brands – that’s where the concept of private dining came from.’

The rooms themselves are ornate, to say the least. One is kitted out with Bentley this and that – from the old leather car seats to the sleek dinner table refashioned from a car dashboard. Another, commissioned by Montblanc, has its place in the record books as the smallest dining room known to man – popular, as Shelley-Anne Claircourt (Press Officer) tells me, as much with proposing couples as with businessmen conducting business deals sous la table.

Then there’s the staircase – probably the most obvious proof of Mosimann’s success. The walls of which are entirely hidden by a montage of framed pictures, and they’re all of Anton posing with the likes of Princess Diana, Andy Murray, Jack Nicholson, Nelson Mandela, and an assortment of celebrities and dignitaries that were all over the papers in the 80s.

Jump To a Section Below

The Bentley Room

They might be famous to us, but what’s famous to them (and what we haven’t got to yet) is Anton Mosimann’s cooking. Shelley-Anne recalls one story in particular. ‘In the 70s the BBC were running a programme called Food & Drink and they challenged him because he’d brought about cuisine naturelle and they said, “so you’ve got this style of cooking, but how do ordinary people eat food like this on a budget?” And he said, “fine, I’ll rise to the challenge. How much? £10? I’ll do it.” So he cooked a lunch for seven for under £10 including a bottle of wine. Bread and butter pudding was the dessert and instead of having a lot of bread, as you would normally, he created a sort of custard consistency. It went down so well that they had 46,000 requests for the recipe. And that was in the days when you had no choice but to write a letter – no emails back then.’

For any restaurant to have a dish like Bread and Butter pudding on their menu for a quarter of a decade is something of a luxury, but Mosimann’s is so steeped in ideologies like family and tradition (Anton even refers to the chefs he’s trained as his ‘children’) that the best dishes don’t need to change. ‘It’s funny,’ says Mark. ‘40% of the dishes on our menu have been there for 25 years as they’re our kind of signature dishes. Some of our members come in not needing to look at the menu and they’ll say, “I’ll have the risotto” or “the steak tartare”. So there are recipes from the kitchen that are sort of sacred and holy.’ Appropriate, then, when your establishment inhabits an old church.

‘As for the other 60%, the chef – who has been with us now for 5 years – has room to play and create within a certain framework, but funnily enough he has a very similar cooking style to father and that’s how we found him. We went to his restaurant and said, “he cooks just like you!” So that helped. He’s also from the same town in which father grew up. He lives and breathes all the concepts we have.’

Mark Mosimann

I hazard to Mark that nothing needs to change too much when you’ve found the perfect dish. ‘The members are the critics. If one has a risotto and something is ever so slightly different about it, they’ll come to me and say so.’ So, I say, there must be some comfort in the fact they know what they’re going to get? ‘That’s it. There’s a profile of those we attract, and we’re aware of what that profile is. They’ll say they’ve gone to every Michelin restaurant left right and centre, but they’ll come back here because they know what they’re going to get. They say there’s food out there that involves these kind of foams and gels – it’s a little too conceptual and modernised when the presentation should be nice and simple. Simple but well cooked.’

Having such a good relationship with your faithful members is part of what makes Mosimann’s Mosimann’s, according to Shelley-Anne. ‘Especially when your guests come forward and give feedback and suggestions. You don’t get that in a restaurant, but here they’ll tell you if they don’t like something or if they want more of it. So you can develop things together.’

‘Funnily enough that’s how our British Pullman event came about,’ says Mark. ‘One man came forward – he’s a hobby train driver in his spare time – and he said “oh Mark, have you considered doing this, maybe it could work?”

Subsequently, the event in question is one of the highlights in the Mosimann calendar. Mark managed to organise a dreamlike collaboration with Belmond and Lanson aboard a 1920s steam locomotive, sister train to the Orient-Express. ‘We love the idea of showcasing the train – well you can’t really call it a train; somehow there are 300 types of wood in one carriage – it’s quite a thing being on the train enough, but the culinary element is designed to add to the experience.’

Philipp, Anton and Mark

And what an experience it promises to be. On a November evening at Victoria, members will be greeted on the dedicated platform with Lanson champagne and canapés. After the train arrives, they board, find their allocated seats and the train sets off across the Kent countryside for four and a half hours. Oh, and while on board guests will dine on a 5-course meal on behalf of Mosimann’s with matching champagne. ‘Everyone will be in dressed in 1920s fashion – it’s all very much in the style of a bygone era,’ says Shelley-Anne.

The plethora of events in the Mosimann calendar certainly enhances their global prestige in the catering industry, but sustaining it isn’t as easy as it is within the UK. Especially when you’re hosting events across the world while trying to summon the right ingredients and retain the quality of your food.

‘We’re so used to it to be honest,’ says Mark. ‘We cook mostly in Switzerland, and by now we know what works and what doesn’t. In terms of the bread and butter pudding recipe – which here has been famous since the late 70s – we cook that in Switzerland and it’s completely different because of the milk fat content and different egg sizes, etcetera, so we have to adapt wherever we go, but we’re very flexible with what we do. It’s a testament to all these events we’ve done abroad that you have to be.’

If you’ve ever had the pleasure of Anton’s take on the staple British dessert, then you’re probably a member of Mosimann’s. And if you’re a member of Mosimann’s, you’ll be aware of the special treatment their regular patrons receive. Anton might not be getting any younger, but Mark is confident his traditions will continue once he hands down the reins.

‘For us it’s important to carry all our ideas on and the members are becoming used to not seeing father around as often, but still know the quality is there. At first it was strange because father used to go come out and shake everyone’s hand, but the members are getting used to not having that.’

He’s still chairman of the company doing more and more promotional events around the world for the company. Since Philipp and I joined we’ve freed up some of his time to go and do these things that he loves. He’s just got back from Moscow where he was cooking for 68 people.’

‘And Tel Aviv,’ chimes in Shelley-Anne. ‘And he was cooking in Zurich for the Pink Ribbon charity. Before that he was in Shanghai speaking at a wedding seminar for 1,000 people. Let’s not forget the Royal Wedding, either.’

‘But when he’s in London he’s still back in the kitchen,’ adds Mark. No less busy, then. It’s almost remarkable that someone of Anton’s vintage manages to summon the energy, but then you forget his cooking is all about fresh and organic produce without the frills, so it’s little wonder, really.

Sebastian is a former hedge fund trader who worked only to indulge his true passion – food.

He has dined at over 240 Michelin-starred restaurants around the world, savoring culinary masterpieces and understanding the stories behind them. He now advises restaurants on menu design, decor and holistic diner experience.